Chris Bohjalian

posted May 15, 2007

Writers write. Right? Well... These days, the literary woodwork fairly crawls with folks more interested in "being a writer" than in actually, you know... writing. Thankfully, to pick up the slack, we can turn to Chris Bohjalian—in the course of less than two decades, he's not only written ten best-selling novels, but won a raft of awards and earned praise from a broad range of critics. And all this while holding down a day job... as a writer, natch: he's been a columnist for the Burlington Free Press since 1992. How does he do it? Readers read—right? Read on, then, and find out...

| * * |

"Laurel Estabrook was nearly raped the fall of her sophomore year of college." So begins the prologue to The Double Bind. Many of your books open with a dramatic "incident." As you develop a story, do you focus on "something happening to someone" or "someone doing something?"

More times than not, the prologue is written when I am well into the novel and I have (finally) figured out what the story is really about. In other words, it isn't usually where I begin.

Without the prologues, my novels would tend to begin rather slowly, with lengthy introductions of characters and places and the issues the book is going to explore.

But by beginning with a gunshot (Before You Know Kindness), a cataclysmic flood (The Buffalo Soldier), and a teen girl watching the jury return with the verdict in her mother's manslaughter trial (Midwives), I can instantly drop the reader into the midst of the story. In addition, when a novel opens in this fashion, it tends to make the first half somewhat more ominous and foreboding. Imagine, for example, the first 120 pages of Before You Know Kindness if you didn't know that Charlotte was going to all but shoot off her father's right arm?

Now, this isn't a formula: I hope there is nothing formulaic about my work and each book is quite different from the one that preceded it. And in the case of The Double Bind, I knew precisely how the book was going to end when I wrote that first sentence you noted in your question, and in this case I DID write the prologue first.

This is a long-winded way of saying I am neither focused on "something happening to someone" or "someone doing something" when I begin a book. If I am focused on anything, it is on character and how different people walk through this world and try to make sense of it.

You've admitted that you "rarely have the slightest idea where [your] books are going." But you've said that The Double Bind was an exception—that you knew from the first exactly how it would begin, and how it would end. Did this make it easier or harder to write than your previous novels? More enjoyable, or less, or enjoyable in a different way?

It was a very different experience. I knew "A" and "Z," but had to figure out what the 24 letters were in-between. Consequently, it was more of a puzzle than my previous novels. Usually, I depend upon my characters to take me by the hand and lead me through the dark of the plot. This time, I felt more as if I had to lead them.

It was, however, no less enjoyable.

You've written about such topics as midwifery, transsexuality, animal rights activism, and foster care, and some have labeled you an "issues novelist." Did you mean from the outset to address homelessness in The Double Bind?

Yes, it was a reviewer for the New York Times who called me an "issues novelist." I liked that.

But it's not precisely that I view my novels as stories about some social problem. I don't. I think a novel written to illuminate an issue would be deadly dull: Imagine a 125,000-word op-ed.

Rather, like everyone else I see subjects out there that interest me. And when I come across a subject I know little about but find compelling, it may indeed work its way into one of my novels. Writing teachers often tell their students to either a) write they know, or b) write about things they don't know. I think you should simply write about things that interest you madly, and if you know little about the topic, then savor the process of research.

So, to answer your question: Yes… sort of.

The Double Bind features a number of photographs taken by Bob "Soupy" Campbell, the real-life inspiration for the character Bobbie Crocker. You've said you decided to include them only after you finished the book, and they bear no direct relation to the narrative. How do you think seeing them might shape the way readers understand Bobbie, and the story as a whole?

First of all, Bob "Soupy" Campbell was not the real-life inspiration for the character Bobbie Crocker. I cannot stress that enough.

His photos were a part of the inspiration for the novel. But Bobbie Crocker bears little in common with Bob Campbell, other than the sorts of things they photographed, and that they both wound up homeless—in Campbell's case, for a brief period.

I put the photos in the book to celebrate Campbell, and remind people that often the homeless have led lives that are vital and vibrant and interesting.

Now, once they were in the book I realized that they accomplished something else: They reinforced the twilight zone fog I was trying to create: A world in which fictional people are treated as real and real people are used fictitiously. After all, readers know these are actual photos taken by an artist who wound up homeless... but that Bobbie Crocker is a fictional construct.

And I liked that. I liked the way it made the experience a little unmooring.

Many writers blur the life/art line by fictionalizing real events, and including real people in their narratives. But in The Double Bind, you've taken the blurring to a new level—you've "factionalized" the fictional world of The Great Gatsby. How did you decide to do this? Did you worry that some Gatsby diehards might refuse to read "The Double Bind," for fear that you'd played too fast and loose with a work they treasure?

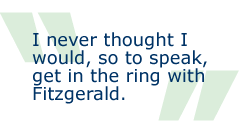

There's a great Hemingway aside in which he remarks that he never wanted to get in the ring with Tolstoy.

I never thought I would, so to speak, get in the ring with Fitzgerald.

I have always loved his work. No one writes sentences as luminescent or as poignant. And The Great Gatsby is one of my very favorite novels.

But when I am writing a novel, I'm not thinking about critics or readers or movie producers. I'm not thinking about anything but the characters and the story I'm trying to tell. Only when I am finished do I begin to ponder how people will respond.

It is also worth noting that the only character from The Great Gatsby who interacts with anyone living in The Double Bind is Pamela Buchanan—who is the toddler referred to as “Pammy” in Fitzgerald’s novel.

It would be an understatement to call The Double Bind's ending an unexpected twist. Without giving too much away, could you tell us, did you consider a more "expected" conclusion?

Nope. I always knew exactly how the book was to going to end.

Now, to answer this question fully, I probably need to tell you considerably more than you need to know. Forgive me.

It was in December 2003 that Rita Markley, the executive director of Burlington’s Committee on Temporary Shelter, shared with me a box of Bob Campbell's photographs. The photos were remarkable, both because of Campbell’s evident talent and because of the subject matter. I recognized the performers—musicians, comedians, actors—and newsmakers in many of them.

I write a weekly column for the Burlington Free Press, which was why Rita wanted me to see the photos. She thought Bob Campbell might make for an interesting story, and she was absolutely right: I wrote about Campbell in December 2003, and to this day it remains one of my favorite essays I’ve written for the paper. I had celebrated Campbell's talents and I had researched his life. But then I thought I was done with the subject.

In June, 2004, I happened to reread The Great Gatsby. Then I went for a bike ride on a dirt road deep in a canopy of woods. My wife had heard a story on the radio that day that advised parents to tell their children the following: If someone ever tried to abduct them while they were riding their bikes, they should hold onto the handlebars for dear life. It's more difficult to abduct someone and throw them into the back of a car or a van if they are firmly attached to their bike.

As I rode, I started thinking about Bob Campbell in regard to The Great Gatsby. Why? Perhaps it’s because we always see The Great Gatsby through a haze of black and white photographs—Campbell’s medium. And, of course, The Great Gatsby" is a jazz age novel—and Campbell photographed a lot of jazz musicians.

And so the idea for "The Double Bind" formed in my head on that dirt road. I knew precisely how the book would begin and—for the only time in my life—I knew precisely how it would end.

You make yourself quite available to your readers, through your website, taking part in local reading groups, and participating in online chats. Does talking to your readers ever make you look at your work differently? Does it shape your writing in some way?

It doesn't consciously shape my writing, because I really am focused only on what is best for the novel when I am at work.

But I do learn how my books have failed in ways I hadn't expected or succeeded in ways I hadn't imagined. And so I hope I am a better novelist as a result of my interactions with readers.

You've said that above all, a writer needs to have a thick skin to succeed. Is there any sort of criticism that gets under your thick skin? Conversely, what sort of praise pleases you most? And does criticism—or praise—of your last work ever shape the way you approach the next one?

I hope I learn from well-meaning criticism. At least I try to.

I find the anonymous critiques that float around the web a little frustrating sometimes. On occasion an anonymous reader will write, "He's no Tom Clancy" and proceed to savage me. Obviously I'm no Tom Clancy. I don't think I've even used the word "submarine" in one of my novels.

You've said that when you start a project, you're filled with excitement, but eventually you become frustrated and have to slog to the finish. Do you always force yourself to complete a book, or do you ever abandon projects halfway through? Do you ever put projects aside, then pick them up again later?

I have three unfinished novels and two finished ones that will never be published. Scott Fitzgerald talked about the dead ends a novelist occasionally confronts, and I have had my share. And that's fine. Sometimes you simply have to reach the end of a story before you can determine whether it is indeed unworkable.

So far I have never gone to back to one of those problematic manuscripts and tried to rescue it. Maybe someday...

You follow a very specific writing routine—you start at five a.m., continuing 'til ten or so, always in your home office, with pen and paper if you're revising, and on the computer if you're doing a first draft or entering changes. How did you develop your routine? Could you write in another place, or without a set routine?

I can write anywhere. I am simply happiest and most productive in my routine.

In college, I wrote in the middle of the night.

I began working in the mornings when I graduated from college and had a day job. Then I wrote fiction from 5 to 7 a.m. before work, and the habit simply stuck.

You moved to Vermont more than twenty years ago, and you've said that your fiction would be much different if you lived somewhere else. What would you be writing if you still lived in Brooklyn Heights?

Hard to say. Perhaps I would have found material that interested me as much as—for instance—midwifery, rural America, and alternative medicine. There's certainly no reason to believe that I would not have written such books as The Double Bind or Trans-sister Radio. But Midwives? Unlikely if I had remained in Brooklyn.

I love New York City, by the way. I get back there as often as I can.

In a recent Post Road interview, you say that before you had your first story published—in Cosmopolitan—you'd had others repeatedly rejected by such magazines as The New Yorker and Harper's. What became of those stories? Were they different from the fiction you write now, and if so, how?

They were train wrecks, one and all. They are in the archives at my alma mater where my papers are stored. My literary executor has instructions never to allow them to be published.

© 2007 failbetter LLC · all rights reserved